Luther Jackson Middle School celebrates its 70th anniversary

Before Luther P. Jackson High School was built, Ronald Reaves was bused from his home in Groveton to Manassas Industrial School. That was in the early 1950s when Fairfax County didn’t have a secondary school for Black students.

He transferred to Jackson High School when it opened in 1954 on Gallows Road. He excelled in sports, as captain of the football team, center on the basketball team, and high jump state champion.

Harry Taylor, a member of the first graduating class and student body president, walked to Jackson High from his home in Merrifield. He recalled the student government’s biggest accomplishment – expanding the interval between classes from two to five minutes.

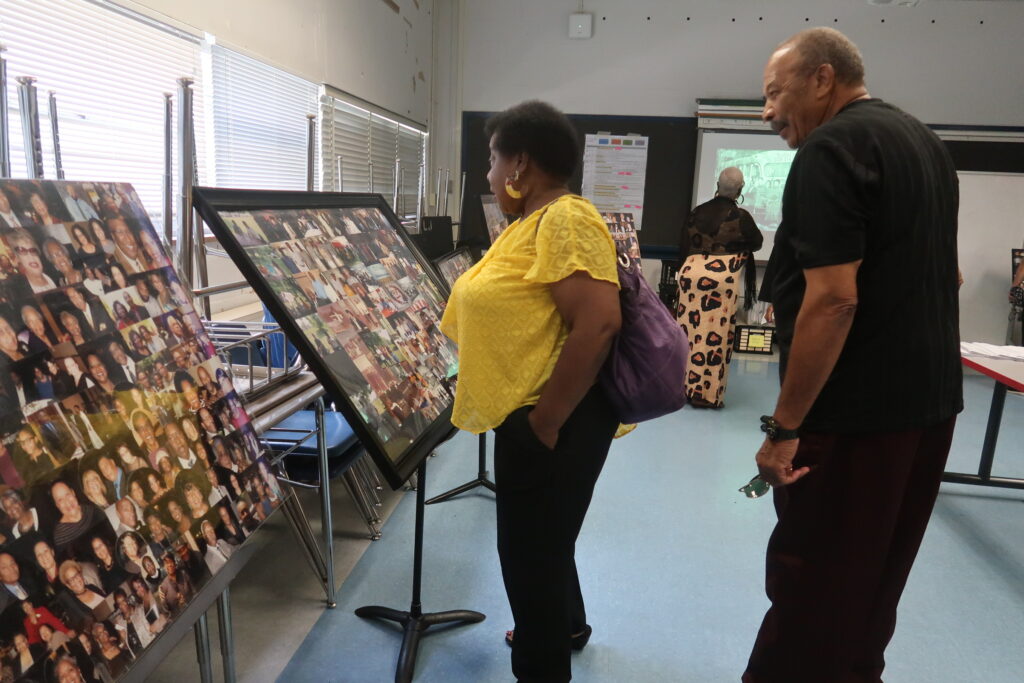

Reaves and Taylor were among the alumni who came to Luther Jackson Middle School on July 14 for the school’s 70th anniversary celebration.

Luther Jackson High School was Fairfax County’s first high school for Blacks. Ten years after it opened, it was converted to an integrated middle school.

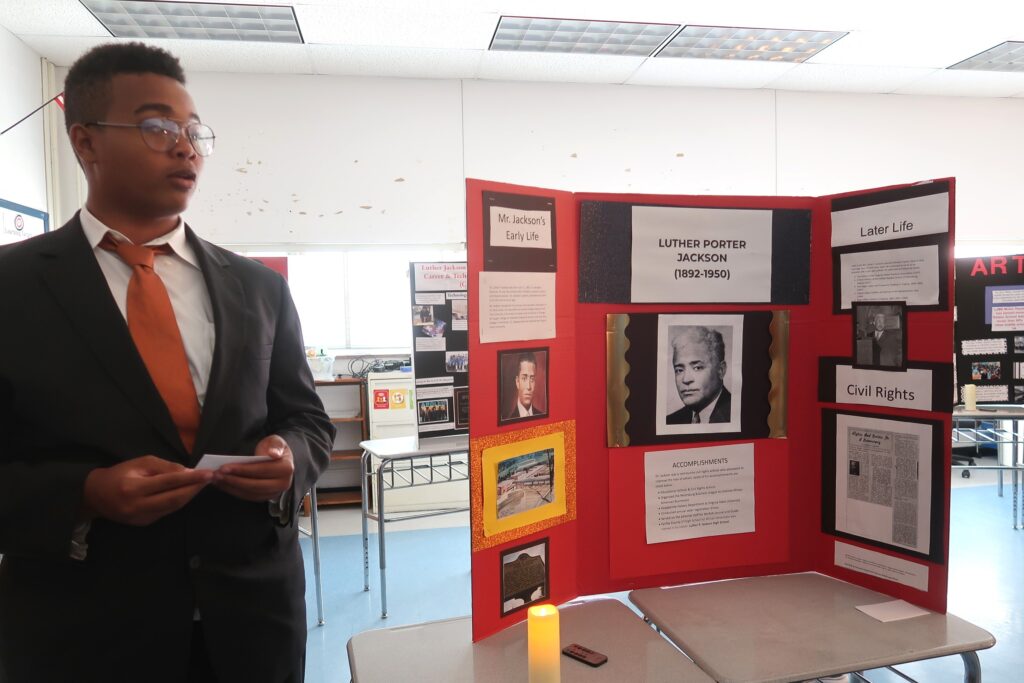

At the anniversary celebration, students hosted a “living wax museum.” They impersonated current and former school leaders and gave brief presentations on their accomplishments.

A sense of community

In addition to alumni, the event drew students, parents, current and former staff, and former students who came back to teach. There was a student art exhibit, songs by students from the school musical, “Matilda,” games and music through the decades, and discussions of the school’s history.

“The sense of community we have here is the most amazing thing about this school,” said Principal Raven Jones, who was recently named FCPS Outstanding New Principal.

“The parents who send their children to Jackson in 2024 are just as hopeful as the parents who sent their children to Jackson 70 years ago,” Jones said. “They tell their children they want them to have more opportunities and a better life than they had.”

The school’s first principal, Taylor Williams knew students “needed a place where they felt welcome, where they felt safe,” Jones said. “They needed to show the world that they could learn at the same high rates of achievement as any other child in Fairfax County. Those goals have not changed. That is the same thing we want to do today.”

The current students at Luther Jackson Middle School represent 40 countries and speak 47 different languages, noted Fairfax County Public Schools Superintendent Michelle Reid.

Referring to the school mascot, Reid said each individual tiger has a different pattern of stripes. “The same could be said about our tigers here. No two children are identical. Each child brings unique gifts, dreams, goals, and hopes.”

“We have to build on the strengths of the past as we envision a better brighter future,” Reid said.

The first Black high school

Barbara Wilks, who attended Luther Jackson when it was a high school, outlined how it came to be.

Until the mid-1950s, Black children had to go high schools in Washington, D.C., or Manassas after the seventh grade – at their own expense – because there were no high schools for Blacks in Fairfax County, Wilks said.

The NAACP, the Fairfax County Citizens Association, the League of Women Voters, and other organizations formed an interracial committee to push for a high school for Blacks.

County voters passed a bond issue in 1950 that included funds for building the Merrifield Colored High School.

The Black community was instrumental in having the school renamed for Luther Porter Jackson, a professor of history at Virginia State College. “He promoted political, civil, and human rights for all people regardless of race,” Wilks said.

The school opened on Sept. 7, 1954, with 712 students.

“Students, community, and staff were overjoyed with their new school,” Wilks said. Because it served Black students from all over Fairfax County, “Luther P. Jackson students experienced a special bond.”

“It was a vibrant school with many activities and organizations, and there was a family atmosphere among students and staff,” she recalled. The school always ranked high in math and science competitions. About half the students went on to college after graduation, and many others pursued vocational education.

On Jan. 14, 1965, the school board decreed that Luther Jackson could no longer be a high school for Blacks. The school reopened the following September as an integrated intermediate school.

In September 1988, it was declared historically significant as the first Black high school in Fairfax County.

Dedicated teachers

In the 1950s, teaching was very different, said social studies teacher Sharon Parker, who was honored as the school’s 2024 outstanding teacher. “Back then there were no computers, projectors, cell phones, or the internet; all teachers had was a chalkboard and a piece of chalk.”

“Despite their challenges, they were dedicated, they were passionate, and no doubt, they had an impact on their students,” Parker said.

In 2024, despite all the technology at teachers’ disposal, there are new challenges, she said. “There’s a constant battle against screen time and an overwhelming amount of information on the internet that we have to help students sort through.”

“While the world has dramatically changed since 1954, one thing remains constant – the importance of education and its power to transform lives,” Parker said.

Luke Caldwell, who just completed the eighth grade at Luther Jackson, spoke about how challenging it was to enter middle school as a seventh-grader. He expressed appreciation for the teachers and the older students who helped him as a lowly “seven.”

“Amazing things are happening at Luther Jackson every day,” said parent Kelly Gould.

It’s not just the school’s hydroponic shed run by the award-winning engineering department, the outstanding music and theater programs, and the Science Olympiad winning teams, she said. “What has left the most memorable impression on me as I walk through the halls is the caring community that I see and hear.”

My thesis adviser at the Columbia School of Journalism was Luther P Jackson, a former Washington Post reporter. He was a good man, and I ve always wondered if Luther Jacckson high school was named after his father. A high honor.