Racial covenants – widespread in Mason District – can be removed

You probably aren’t aware of this but if you’re a homeowner in the Annandale/Mason District area, there’s a strong likelihood that your property has a restrictive covenant prohibiting non-White ownership.

Racial covenants are illegal and non-enforceable, but many are still in the deed books.

The Fairfax County Board of Supervisors approved a Board Matter in September directing the county attorney to file a formal release of such covenants in the county’s land records. It also directed staff, in coordination with the Clerk of Court, to review other property deeds to county-owned properties to identify any additional unlawful racial covenants.

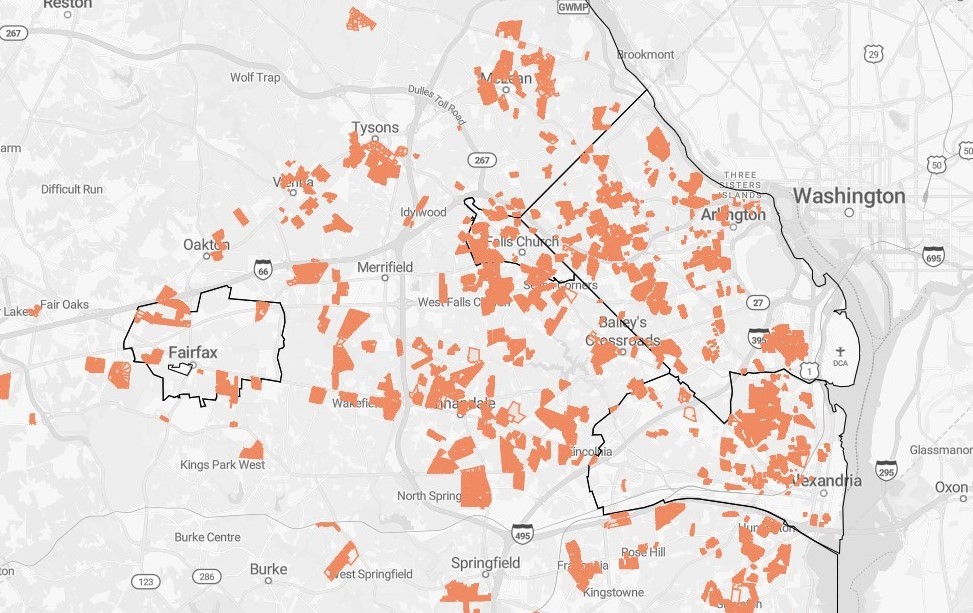

To see if your property has a racial covenant, look up your neighborhood on this map.

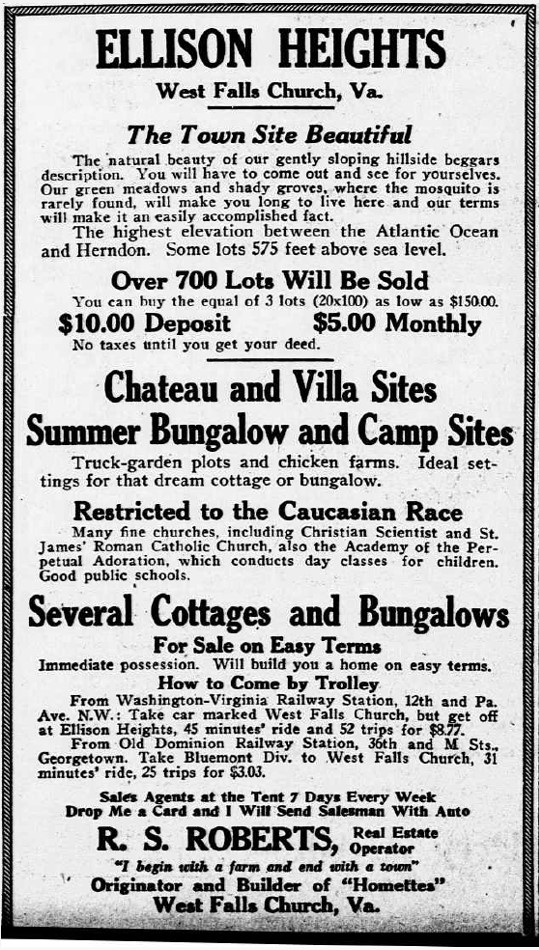

Here are some examples:

- A covenant for Courtland Park in Bailey’s Crossroads approved in 1938 states: “That the said lots or any interest therein shall not be sold, leased, conveyed, devised to or occupy by any person not of the Caucasian Race.”

- A covenant recorded in 1948 for Lincolnia Park states: “No one of said lots, nor any parts thereof, shall ever be sold, leased, devised, or conveyed to anyone not of the Caucasian Race.”

- A 1940 covenant for Accotink Heights in Annandale bars any lots from being “occupied by, sold, leased, devised, conveyed or in any manner alienated to any person of the Negro race,” with an exception for “domestic servants of the Negro race.”

Among the many other neighborhoods in Annandale/Mason District with racial covenants: Columbia Pines, Alpine, Annandale Acres, and Strathmeade Springs in Annandale; Pinecrest in Lincolnia; Ravenwood and Buffalo Hill in Seven Corners; Rock Spring in Bailey’s Crossroads; and Westlawn in Falls Church.

In the Northern Virginia suburbs, racial covenants in property deeds were one of the ways segregated neighborhoods were created in Fairfax County from the early 1900s until they were prohibited by the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

The board matter was sponsored by Supervisor Dan Storck (Mount Vernon) jointly with other supervisors.

“This legacy of racial discrimination is a stain on our communities that historically will never go away,” Storck told Annandale Today. “While Virginia Code § 36-96.6 declares that racial covenants are void by operation of law, and while the county could not and would not seek to enforce them under any circumstance, my colleagues and I were compelled to go further to right this injustice.”

“We directed county staff to research and remove these covenants from all county-owned land deeds, as well as educate the community as to how to remove racial covenants from their own land deeds,” Storck said.

Storck and Supervisor Rodney Lusk (Franconia) had attended a lecture this summer on racial covenants in Fairfax County by Krystyn Moon, a professor of history and American studies at the University of Mary Washington.

When Moon started researching racial covenants, she was surprised there are so many.

Racial covenants spread in Northern Virginia in conjunction with the growth of suburbanization in the 1930s and 40s, Moon said. That growth was spurred by the expansion of the federal government and increased road building.

Many subdivisions were built in the inner suburbs, such as Annandale, during that period, so those neighborhoods are more likely to have racial covenants than newer neighborhoods farther out.

At a workshop in October hosted by Virginia Senate Majority Leader Scott Surovell and Del. Paul Krizek, Moon discussed the history of racial covenants and explained how to remove them.

A law enacted by the Virginia legislature in 2020 made the process a little easier, she said. But homeowners still have to search for the original deed with the offending language, record the page in the deed book, and fill out a legal form from the Fairfax County Circuit Court.

Any individual can do this for their own property, but you can’t do it for someone else’s property, Moon said.

If you want to remove a covenant for a whole neighborhood, all the residents have to sign a legal instrument and they will need a real estate attorney.

Moon found one instance of an Annandale neighborhood that had done this. William Smar developed Elcino Manor – consisting of 11 homes on Willow Run Drive – in 1951. He had the racial covenant removed in 1954.

“The response from the community at the workshop was pretty positive,” Moon said. That session highlighted how systemic racial covenants were. “It’s hard to see how systemic it is unless you actually map it. That makes it much more impactful.”

Moon’s racial covenant identification project, “Exclusion & Resilience in NoVA,” is a work in progress, with more covenants expected to be added to the map. Moon and her colleagues at Mary Washington are part of the National Covenants Research Coalition, which is documenting the history of exclusion nationwide.

The legacy of racial covenants are still with us, Moon said. “Those deeds rolled back any momentum for Black residents to become renters or homeowners in Fairfax County.”

Racial covenants were just one of the tools used to maintain segregation, she said, along with road expansion that divided communities, zoning ordinances, eminent domain for the construction of schools, public housing construction, and restricted access to mortgages.

When Little River Turnpike was widened and Interstate 395 was built, African American homeowners were displaced. “When they lost property to those projects, it’s not like they could buy property elsewhere,” Moon said.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer in 1948 that racial covenants were legal, but unenforceable. “That started to unravel his process,” she said.

The most recent racial covenant Moon found in Fairfax County was in 1957 in Chesterbrook Woods in McLean. The most recent one in the City of Alexandria was recorded in 1962.

The federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 made racial covenants illegal along with other forms of discrimination. Fairfax County passed its own fair housing rule a few months later, with an “open occupancy ordinance.” Virginia enacted a fair housing law in 1972.

This is a non story – the racial covenants are not enforcable.

It’s not a non story for the offspring of the african american owners who had their property taken through eminent domain to create these white only neighborhoods.

It’s a story because it is our history, but according to the article some black property owners were displaced due to highway construction, not to create white only neighborhoods. There were also black landowners who sold their property to developers. It would be interesting to know if those parcels, once subdivided, had racial covenants.

Black communities were targets for government takeovers — only governments can exercise eminent domain — for supposed public purposes, notably both schools and roads. The Woodburn area near Inova Fairfax in the 1950s housed a Black community of about 30 homes. The School Board knew most Black homeowners would not trust courts to ensure they got the legally required fair market value for their land, and would accept whatever pittance was offered. So the schools could take over the land cheaply. It turned out Woodburn was never needed for a school, and at least some of it became parkland, but the history of some other school sites was similar.

I hope many home owners will do this.

Absolutely fascinating, Ellie. Thank you so much for this article.

Thank you for this information. When we purchased our house back in 1988 we did our own deed search and found these covenants on the property. I was happy when I followed up and determined that they were unenforceable. With this new information, I will definitely work to remove the covenant; it has always been a horrific reminder of how things were in Virginia.

When I bought my first home in Arlington in 1979, I found a restriction on Negroes and Jews in the deed before signing the sales contract. I asked about it and was discouraged by the attorneys from removing the clause. Was told it would cost a ridiculous amount of extra money and effort and would hold up the closing. I to this day do not understand why such language could not be easily struck when purchasing the home. For those who wonder. why it matters if it is not enforceable – it is a constant reminder and specific threat against race and religion. Nobody should have to deal with that. All jurisdictions should update all deeds to remove such language. It should not require individuals to file their own paperwork.

Thank you for shedding light on this piece of history. While not enforceable, it was at one point! Why else would they have been written in the first place? The 50s and 60s were not so long ago…

It would be nice if the general assembly investigated passing a law that would allow those covenants that have been deemed unenforceable and illegal to be automatically removed during the next home transaction – or at least allowing localities to pass a local code specifying the same.

This kind of thing should not be put upon individuals to have to pursue out of their own conscience (though kudos to those who do), and the next home transaction when the deed is updated makes sense to take advantage of the paperwork being refiled anyways. Doing so at that time likely would just be a few hundred dollars max additional to the final cost of closing.

It does appear that from the state law passed in 2020 that amended the Code of Virginia section 55.1-300.1. “Certificate of Release of Certain Prohibited Covenants” that lets one file a certificate to have the covenant removed there is a courts form at https://www.vacourts.gov/static/forms/circuit/cc1508.pdf

And there is county information on how to fill in and file deed forms at https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/circuit/land-records/land-records-faq

For the law see https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacodefull/title55.1/chapter3/#:~:text=Certificate%20of%20Release%20of%20Certain%20Prohibited%20Covenants.&text=The%20covenant%20contained%20in%20the,A%20of%20%C2%A7%2036%2D96.6.

How do we begin a campaign to propose a law such as the one spelled out by Jeffrey Longo?

Thank you for this article. Local press makes the citizenry better for being informed. The comment about the burden and cost of removing the restrictive covenants by the homeowner is enlightening, which makes the removal of these terrible covenants, regardless of enforceability, a step towards righting a wrong. If we do nothing about these archane laws and regulations we tacitly accept them.