They built the road they would be forced to walk: a brief history of Little River Turnpike

From my front porch, looking over my garden, I can see the two blocks to the intersection of my street with the Little River Turnpike here in Lincolnia. I typically walk there once a day or so on my way to the local coffee shop or to Green Spring Gardens, a stunning horticultural center that reminds me of why I live here in Fairfax County. All in all, it is an idyllic life – early 21st-century troubles notwithstanding.

Little River Turnpike carries its history in its name. It was the turnpike – the toll road – that led to the Little River, some 34 miles to the west. One of the first-ever roads constructed in this country, it stretched from Alexandria through farm and field countryside. Today it has many names along the way, but right here in Annandale, it is still called the Little River Turnpike.

|

| Stone bridge at Aldie, the end of the turnpike. |

Although its six-lanes are not often loved, its history is indelibly connected to the counties it passes through. But that history – of sleepy farmers on slow carts, bearing their produce to the wharves of Alexandria – is really just one side, one happy side, of the road’s past.

The rest of its history is something that I suspect few in my area know about. For the Little River Turnpike is a road built by enslaved Americans that served, eventually, as the path their children and their children’s children, would take when shackled at the feet, they were marched away from their homes to the Deep South.

When I look up the street to the Turnpike, I see only cars racing by on their way to Alexandria, about four miles to the east. Like so many roads, we don’t see really see it. We see cars, bicycles, stoplights, street signs, storefronts, but we don’t see what went into the making of the road – why it went here, who did the work, and what happened to them.

The Turnpike was an incredible challenge – the structure of the road itself was very modern, very expensive, and very arduous. Since this was early 19th century Virginia, the builders turned to the labor market they were comfortable exploiting: enslaved Americans who were to be rented under contract.

Twenty men were retained to do the work of the overseers over the next few years. The proceeds of the work did not go to those who did the actual work; no, that money went to those who enslaved them. Although we have never really listened to their voices, the workers clearly spoke – a number ran away from the job, a number large enough that they had to find another group to keep the work going.

In my mind’s eye, I can see the men clearing fences and trees out of the way, shoveling the soil to build the mounded center of the roadway and then sloping it away from the crown. Stones had to be lain just so, so water would drain; ditches would need to be dug to carry water away. The road had to be dry – or at least mostly dry – so that the mud that bedeviled so much cartage and horses in that day wouldn’t impede travel and justify the 10-cent tolls.

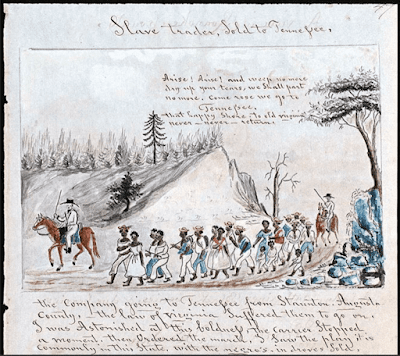

|

| A coffle of slaves being marched from Virginia west into Tennessee, c. 1850. [Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation] |

The climate in Virginia can be terribly hot or numbingly cold – there is no doubt in my mind that the overseers would not care too much about the comfort of their workers. The task at hand had to be completed.

It took eight years of hard work until December 1811 when the final pieces were put in place. From that point, the road became a major thoroughfare, one so popular that towns sprang up along its path and shaped the infrastructure that underpins Northern Virginia.

One can look at a map of the whole area and still trace the straight line that was the Little River Turnpike, now routes 236 and 50, from the city to the hills. The road became the backbone of transportation from the Piedmont and the Shenandoah Valley to the waterfront of Alexandria.

Because the road was so efficient a mover of produce and carts, it also served to move men, women, and children from what was called the Tidewater all the way to Louisiana and Mississippi.

Once the nation had restricted the “slave trade” – the seizure of humans from Ghana, Senegal, Biafra, Congo, Angola, and other places – and the nature of agriculture in the young country had shifted from tobacco in the mid-Atlantic to cotton in the Deep South, the demands of labor also shifted.

White landowners in Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas found a new way to profit – many had their enslaved workers sold to cotton slave camps in the south. Families were broken up, children separated from adults, communities shattered as merchants of the enslaved found what is now called the “domestic trade” to be a profitable exercise.

In Alexandria, prisons full of these men and women were used to house them while sales could take place. These prisons still stand along Duke Street in Alexandria. From these prisons, the enslaved were either sent by boat to New Orleans or shackled together in “coffles” and walked overland to Louisiana.

To describe the experience of the coffles would be impossible without falling prey to minimizing the horror. For our discussion, however, it is the passage itself that concerns. For those prisons sent the enslaved in coffles to trudge down Duke Street, the starting point of the Little River Turnpike. From the prisons, the coffled men and women would ascend towards Shuters Hill and the Turnpike. The last stop: New Orleans.

Bound together, moving slowly, the groups of enslaved would probably manage about 20 miles a day. If they left early in the morning, they would be reaching the outskirts of Green Springs Farm in Lincolnia (then Uniontown) probably mid-morning. Coming up the Little River Turnpike where it crests the hill after Turkeycock Run, they would walk along the field of the large farm, the promise of water from its fresh spring perhaps used to entice them to quicken their pace.

If one of those walking in shackles looked to the left, they would see fields of corn and maybe a small orchard, looking right at the place my house would be built in another hundred years. They might see other enslaved Americans working in those fields, fields that were now poor after long periods of cultivation, workers straining in the sun. They might have looked at each other – both enslaved in the only land they had known right there where Cherokee Avenue meets Little River Turnpike, where a dentist and a daycare center now watch the car dealer across the street. They might have wondered what would become of the other?

|

| The Historic House at Green Spring Gardens. |

And like that, they would part, one to his plow the other to the stony path ahead of him. At some point in those years, the continuous passage of these thousands of enslaved men and women trafficked to the South, would get less attention. Maybe the workers in the fields wouldn’t even look up much anymore – just another group moving past, like so many before. Or maybe they would be glad that they were not being torn from their families, their children.

I think about this a lot as I walk along Little River Turnpike, nearly 200 years after that time. Only a little of that time remains – the beautiful house of Green Springs that was there before the Turnpike was built now hidden behind the car dealer, the streams that still flow to this day at the foot of the hill, the hills themselves that posed a serious challenge to the builders. Even those people who worked in the fields, remain. For their descendants, who surely settled in this area after the Civil War was fought for them. Lincolnia, just down the way on Little River Turnpike, was primarily a Black American community, with a school, stores, churches, and a cemetery.

The decimation of the American community brought on by the domestic trade of the enslaved remains a central character in the nature of our country. So, in a way, the story of the road that edges my neighborhood is both a story of the past and a story of the future.

Much of the factual basis for this post (but not the opinions) comes from an article from 2017 by Debbie Robison in local history blog, Northern Virginia Notes, an article by the renowned historian Edward Ball, “The Slavery Trail of Tears” in Smithsonian, and Edward Baptiste‘s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism.

It is my recollection that the National Turnpike (US Rte. 40) was built by laying felled tree trunks parallel to each other crosswise across the roadway to form the road. Is there any information that LRT was built in this way?

Also, the naming of LRT now seems to end at the eastern border of Fairfax city, where it becomes Main Street, the Fairfax Blvd, then Lee-Jackson Highway. Does the LRT appellation return at some point? If the naming of Lee-Jackson highway is reconsidered, would the LRT name be re-applied?

Excellent thought provoking article. BRAVO !

Thank you for recounting this important history. It is critical that everyone know who actually built this country. (I think of the slaves who built the White House.) Also, I would like to see photos, especially of Lincolnia, and will look in the sources you cite.

This was a most excellent read! Thank you for the enlightening history lesson.

WOW ! I was stunned to read, and so bothered I've lived here for 20 years and wasn't aware. We need a trail of tears commemoration, including markers, public art, storytelling events and more. Thank you Mr. Albright.

MR

Fairfax County published a book titled, "Fairfax County Stories 1607-2007". My friend, the late Mary Margaret Pence provided "A History of Lincolnia" in that book. Photos included.

Thanks for the article. We have lived in Annandale for over 15 years since we moved from NJ. Nice to know local history

James, for the past few months I have been developing a proposal for a historic marker in Fairfax at the historic County Courthouse to commorate enslaved people who were forced up Little River Turnpike. The proposal is currently being reviewed by the Fairfax County Historical Commission. One of the sponsors for the project alerted me to your blog. So in the interest of education, I thought I could add a few facts about what is known about the "Slavery trail of tears" on Little River Turnpike.

As you mention, men, women, and children were chained together into "coffles" – usually two-by-two. Very young children rode in the wagons. 1315 Duke Street once housed the largest and most profitable domestic slave trading firm in America. It's worth a visit (currently called the Freedom House). The Franklin and Armfield Company (F&A), headquartered here from 1828 to 1836, was one of the largest and wealthiest slave trading firms in country. At its peak, the business was transporting 1,800 slaves a year to Louisiana and Mississippi by boat and overland coffle. Armfield’s partner, Isaac Franklin, was based in Natchez, MS, home of the largest slave market at the time. Armfield regularly sent slaves to Natchez by overland coffles each summer.

I was also inspired by the 2015 Smithsonian article. However, there is no direct accounts (so far) of enslaved people being forced up Little River Turnpike. The Office of Historic Alexandria is currently researching this. But we do have strong indirect evidence. A traveling geologist, Feathstonehaugh, in 1844 wrote of a camp of 300 slaves from Alexandria at a crossing of the New River, near Christianburg, VA and headed to Natchez, MS. So we know the coffle reported by Featherstonehaugh in southwestern Virginia started in Alexandria and ended up in Natchez. The slave markets in Natchez and New Orleans were the destinations for F&A as well as for subsequent slave traders in Alexandria. By consulting contemporary road maps, the coffle would have had to head westward to the mountains and then southwest along them to reach the New River crossing. Leaving Alexandria by land during this time, the likely choice was to go west to Fairfax Courthouse and from there continuing along Little River Turnpike northwest to Winchester or take the Warrenton Turnpike (now Chainbridge Road) southwest to Warrenton or Fredericksburg. An alternative overland route could go north to DC, northwest to Leesburg and then Harpers Ferry (though this was less likely as DC had outlawed the slave trade). Slave traders from Alexandria had additional reasons to go west through Warrenton and Winchester. Both of these towns were hubs of slave trading and F&A had agents throughout the region who are trafficking enslaved people.

I can add a couple more references (both in the Fairfax Library) for people interested in the magnitude and impact of the domestic slave trade on black families. ".. this new interregional commerce in slaves turned human property into one of the most valuable forms of investment in the country, second only to land." (Deyle)

Deyle, Steven (2005), Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in America. Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016

Dunaway, Wilma (2003). The African-American Family in Slavery and Emancipation, Cambridge University Press, 40 W 20th St, New York, NY 10011. 2003

It breaks my heart that I grew up here in Lincolnia. I remember wondering why the road across from Parklawn school where the black families lived looked like shit!!☹️