Guests at new Bailey’s shelter share their stories of homelessness

|

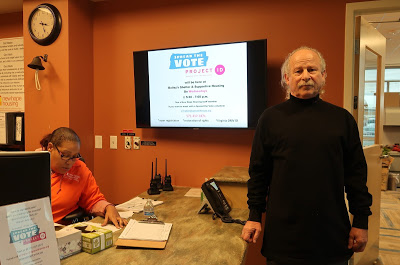

| Robert, a guest at the new Bailey’s shelter, at the reception desk. |

Relationships gone bad, alcoholism, overwhelming grief, and bad luck – those are some of the reasons people ended up at the new homeless shelter on Seminary Road in Bailey’s Crossroads.

The brand-new Bailey’s Crossroads Shelter and Supportive Housing, as the facility is officially known, opened earlier this month. The community got a chance to tour the shelter Nov. 23 at an open house hosted by New Hope Housing, the organization contracted by Fairfax County to operate the shelter.

The emergency beds at the new homeless shelter are fully occupied, mostly by people who were transferred there from the old shelter. The shelter is also providing a warm place to sleep as part of Fairfax County Hypothermia Prevention Program. About 60 people, who could otherwise freeze to death outdoors in the winter, are provided a mat, blanket, and a place on the floor to spend the night.

See blog story: New Bailey’s shelter serves most vulnerable members of the community

In a departure from the old shelter, the new facility has 18 apartments on its top floor where formerly homeless people can live as long as they need to as they work toward full independence. Those units, and the shelter’s four medical beds, won’t be occupied until the shelter is fully staffed.

At the open house, several shelter guests agreed to share their stories with the Annandale Blog.

A toxic relationship

Mark, 33, who spent the previous night at the shelter with the hypothermia program, became homeless after he made the decision to get out of a bad relationship a couple of weeks ago. “I chose to leave because it was toxic,” he says. “I couldn’t deal with it anymore.” Both he and his partner have mental health issues, but he is being treated, and she is not, he says.

|

| Mark hangs out with other hypothermia program clients in the Shelter’s common room/dining hall. |

“There’s a bright side to everything,” Mark says. In this case, “I don’t have to deal with that individual anymore.” On the negative side, he misses her children from a previous marriage.

He had done construction work and IT recruiting in the past but hadn’t worked recently because his former partner was the breadwinner and didn’t want him to work or go to school. He was okay with being a stay-at-home dad, but he hadn’t had any money saved up, so when he left the relationship, he didn’t have anywhere to live.

Mark had stayed in a shelter before, about 10 years in Philadelphia, where he grew up. He had a rough childhood; his parents died when he was a young teenager and he was raised by an older sister. She has 13 children of her own, so he won’t try to move in with her.

People in the hypothermia program get hot meals as well as a chance to take a shower and do laundry, Mark says. Bedtime is 11 p.m., and they are woken up before dawn on weekdays and 7:30 a.m. on weekends. During the day, people hang out in the common room and sometimes get hired for construction or odd jobs for the day.

Mark would like to get a regular bunk at the shelter but it’s full. Meanwhile, he’s hoping to get a job and a room somewhere, save some money, and “start to build a new life.” He has some job interviews lined up but realizes getting back on his feet is going to be “a bit of a struggle.”

A corporate job

Ryan, who’s also staying at the shelter in the hypothermia program, just started a professional job with a major corporation in D.C., which he hopes will be the ticket out of homelessness.

He had been working for the government, but has been out of work for the past two years, he says, because, “I couldn’t deal working with the Trump Administration.”

After his money ran out, Ryan stayed with friends for a while, but found that people are uncomfortable with a longtime guest. His wife passed away a long time ago, and he doesn’t have any family who could help.

He was sleeping outside a church in Fairfax County when a shelter worker found him a week ago and told him about the hypothermia program.

He takes a bus to his job and doesn’t want his employer to know he is homeless. He doesn’t want his children to know he is homeless either. They are staying with a friend.

Marriage troubles

Another man sleeping at the shelter in the hypothermia program, ended up homeless because of a relationship gone bad. His wife kicked him out of their home four months ago after 16 years of marriage. After he ran out of people to say with, he’d been sleeping in his car.

After calling around, he found a spot in the shelter’s hypothermia program the previous night. “It’s hard when you’re used to being on your own and having a bed to having to sleep on the floor,” he says. On the plus side, “I have a roof over my head,” but the downside is “having to deal with a lot of people.”

He used to drive a tow truck and before that, did commercial plumbing work in another state for 12 years. He would like to get back into plumbing, but says, in Virginia, he would need to get a certification. He is considering getting the training needed for certification but his first priority is “getting my own place.”

Overcome by grief

Robert, 57, has been staying in a bunk bed at the shelter since July. He hopes to be able to move to an apartment in Seven Corners as soon as his application for a housing voucher is approved by the county. He plans to use Social Security benefits to pay for his share of the rent.

“It’s been a rough three years,” Robert says, since his wife, Jodi, passed away, from complications following a gastric bypass operation.

They met at the old Bailey’s Crossroads homeless shelter – they both had drinking issues – and were together for 16 years. Robert, a Navy veteran, also is bipolar and has PTSD.

Case workers with the Community Services Board and New Hope Housing helped them get an apartment. In 2016, they moved to West Virginia to take advantage of the state’s health benefits, but Jodi’s condition worsened, and she died a month later.

“Jodi changed me in a lot of ways for the better,” Robert says. The whole time they were together, they stopped drinking.

But after she was gone, “the grief took over,” and he began self-medicating with alcohol. “I knew I was lost and didn’t know what to do,” he says. “Frankly, I gave up.”

He moved to Indiana to stay with a childhood friend. “I tried to get my life together but things got worse.” He missed his daughter and grandson and was hospitalized in Indiana for alcoholism and for being suicidal.

He moved in with his daughter in a small town in Virginia and helped care for her son. But then, during the holidays in December 2018, he started drinking again. He moved back to Northern Virginia in February and secured a bed in a homeless shelter in Reston.

After experiencing the DTs and hallucinations, he was hospitalized in June for a mental breakdown and went through detox.

His path to recovery began when he reached out to the Community Services Board, which helped him get medications and disability benefits.

Robert says the new Bailey’s shelter is much better than the old one. “The beds are more comfortable, and the atmosphere is more positive. When people come in drunk and unruly, they don’t tolerate it here.”

“Today, I’m in a lot better place than I was a few years ago, at least mentally,” Robert says. “I’ve made a lot of progress.”

Physically, he could be better. He has difficulty walking, due to arthritis, and will eventually need a knee replacement. He had worked as an auto mechanic until he was 53 but had to quit when his knees gave out.

He is grateful for the help he’s been getting from his case manager at the shelter. “He has my best interests at heart.”

thank you for doing this

Now in 2025, The homeless (Staff included) smoke marijuana in the building all the time, There are fights all the time (no one is banned & rarely the police are called), homeless gangs tries to beat people up! STAY AWAY FROM THIS VERY, VERY BAD SHELTER!!!